History and modern challenges of rapeseed breeding

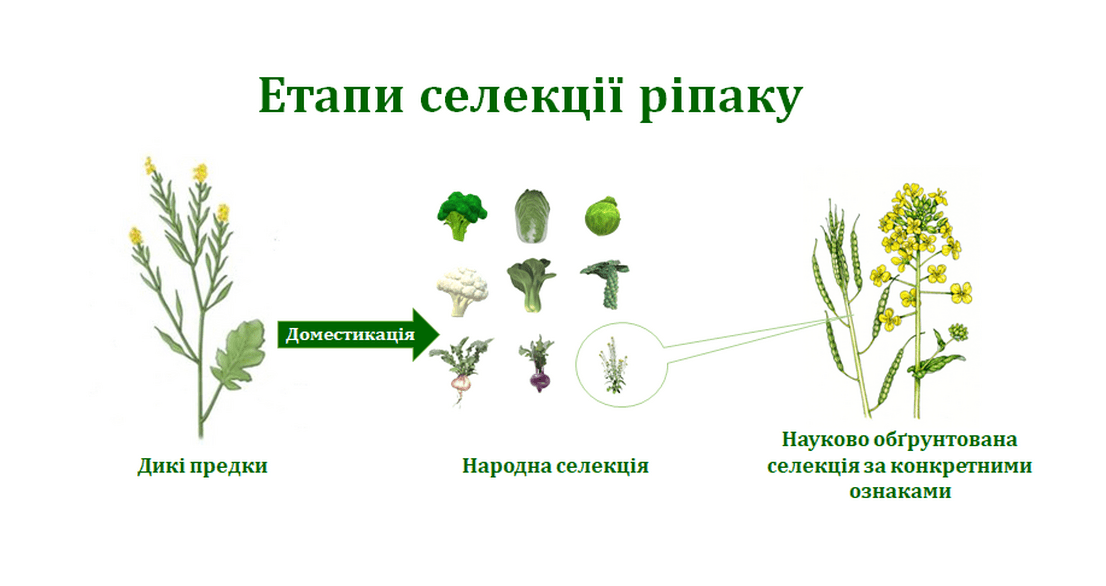

Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) is an oilseed crop that people in Europe and Asia have been growing for thousands of years. According to M.I. Vavilov's classification, rapeseed is native to the Mediterranean region, and China is considered the second center of rapeseed origin. Rapeseed breeding, as with other crops, has several stages. The first is domestication or domestication. This is essentially the period when crop production as such was born, when people moved from harvesting wild plants in their natural habitats to growing them near their homes. Domestication was followed by the so-called folk selection, which was based on an empirical approach. This period in breeding was the longest and was mainly aimed at increasing yields and product quality. Scientifically based breeding is the final stage of breeding development, which continues to this day, although the set of tools used has expanded significantly.

Rapeseed belongs to the botanical family of cabbage crops, and if we trace its path from a wild plant to the present, we can identify several turning points that have determined the future of this crop for tens or even hundreds of years. During the period of domestication, different groups of plant species were distinguished from the cabbage family depending on their use: leafy (salads, cabbage), root (radishes, turnips, turnips, etc.), and oilseed (rapeseed, mustard, camelina, etc.).

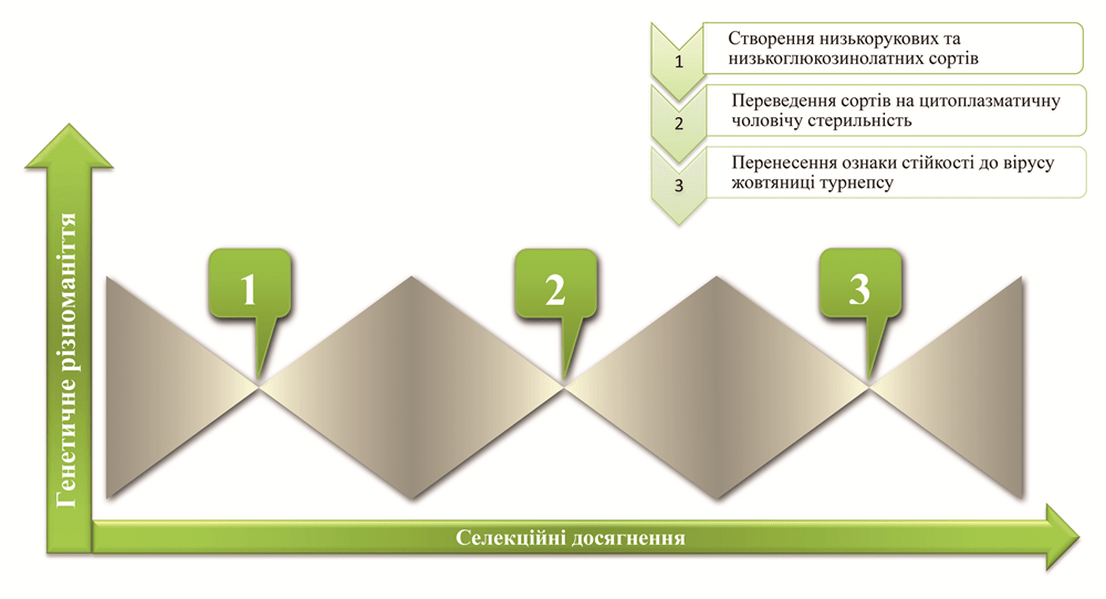

Every important breeding achievement causes a significant reduction in genetic diversity. The more important the achievement is in economic terms, the more the narrowing occurs, and bottlenecks, the so-called “bottle necks,” are formed. This happens because a critical trait is introduced into the entire genetic diversity of a crop by crossing different varieties or lines with a single known donor of the trait, thus creating a strong affinity of genetic material, which in turn leads to a decrease in variability and heterosis. The 60s of the last century, when all rapeseed varieties were switched to a two-zero basis, i.e. with a reduced content of erucic acid in oil and glucosinolates in meal, was the first bottleneck. The next step was to transfer varieties to cytoplasmic male sterility. Nowadays, resistance to the turnip jaundice virus is a relevant trait for European farmers. Over the past two years, every major breeding company has developed at least one rapeseed hybrid resistant to this virus.

Turnip yellows virus (TuYV) is one of the most damaging viruses in rapeseed crops. The main danger of this disease is that the infection of plants occurs in the fall, and the first symptoms of the disease appear in the spring, after the resumption of vegetation. It is also not always possible to diagnose the disease, as the symptoms are very similar to those caused by a deficiency of certain nutrients. Thus, in the spring we have visually healthy rapeseed, possibly with some lack of mineral nutrients, but in fact the entire crop is already affected by the disease, which can reduce yields by 30% or even more.

How to recognize a viral disease?

As a rule, the edges of the leaves on affected plants turn red or purple, while the leaf blade itself becomes mosaic, with light yellow spotting and lightening of the veins. Initially, symptoms are visible only on the lower older leaves, but later in the summer they become more pronounced and can be seen on younger leaves. Infected plants become stunted, have thinner stems compared to healthy plants, form fewer inflorescences, and fewer seeds are set in the pods.

The main carrier of the virus is aphids, with about 70% of the population carrying the virus. The spread of TuYV is also facilitated by warm, mild winters, which means longer periods of aphid activity and, accordingly, an increase in the population of this pest. The ban on seed treatment with neonicotinoid insecticides had a significant impact on the degree of infection of rapeseed crops.

Seed treatment with neonicotinoid insecticides allows growers to reduce the aphid population by 85% and significantly reduce the spread of the virus when the crop is at its most vulnerable stage. Since 2013, the two main neonicotinoids - clothianidin and imidacloprid - have been banned in the European Union for use in open spaces, so only contact-acting insecticides are used. Among the pyrethroid insecticides against aphids, drugs based on pimethrosin or thiacloprid are effectively used

Identification and introduction of TuYV resistance genes into the culture is an alternative strategy to combat this viral disease. Partial resistance to the virus was found in the resynthesized (obtained by artificially crossing Chinese cabbage and rape) line “R54”, as well as in the Korean spring rape variety “Yudal”. These two sources of resistance have different origins, but in both, the resistance trait is inherited as a dominant trait. No genotype has been identified among the entire rapeseed diversity that is completely resistant. However, the partial resistance transmitted from the two sources mentioned above ensures that the crop is harvested without losses due to the disease.

One of the possible ways to fight the virus may be to use biotechnological methods. By analogy with the creation of plants resistant to herbicides or insect pests, it is possible to create forms that are completely resistant to viruses, including the turnip yellow virus. Today, biotechnological methods of genetic improvement of agricultural plants have greatly expanded the capabilities of breeders and geneticists compared to the last decade. Over the past few years, very precise editing of plant genes has become possible without significant changes in non-target genomic regions. In order to clearly explain what the essence of editing individual genes is, we can draw a certain analogy with editing text. The genetic code is usually written in the form of four letters: A, T, G, and C - this is the genetic alphabet. Just as in language letters form words, so in genetics letters form genes. The previous generation of biotechnological methods of plant improvement involved manipulating entire genes, or words. Modern methods involve manipulating individual letters.

Specialists at the Plant Biotechnology Department of the Ukrainian Scientific Institute of Breeding (VNIS) use the CRISPR/CAS gene editing technique to create new rape starting material. New lines resistant to continuous herbicides are being tested in the laboratory. During 2019, in different regions of Ukraine, the Institute's virologists selected virus-infected rapeseed plants to isolate local races of the virus. Based on the isolated materials, genetic constructs have been developed that will ensure full plant resistance to the virus. In addition to the increased level of resistance to the virus, this will solve the problem of genetic material relatedness, which occurs every time a new important trait is integrated into the entire genetic diversity of rapeseed. Currently, VNIS breeders are testing a rapeseed line resistant to turnip yellow streak virus.

Choose a country

Choose a country